Annalee Newitz’s new sci-fi novel covers everything from robot gender to the perfect noodle

If Annalee Newitz’s science fiction novels came with relationship status tags, they’d invariably all be labeled “It’s complicated.” Newitz tells approachable stories where characters face external conflicts, but those characters might be humans, robots, autonomous drones, sapient moose or cats or mole rats, or even odder things. And the external conflicts tend to feel secondary next to the many murkier internal conflicts, as those characters navigate their own identities — particularly their genders, sexualities, romantic interests, and roles within societies that often disapprove of them having any of these things.

In Newitz’s three previous novels (2017’s far-future dystopian thriller Autonomous, 2019’s time-travel adventure The Future of Another Timeline, and 2023’s sprawling further-future saga The Terraformers), these kinds of self-explorations stir up frustration, longing, and revelations. All three books touch on familiar present-day issues around technology, ethics, community-building, and self-definition, but they project those issues onto speculative new worlds. And they’re all written with a rigorous intellectual curiosity that hints at Newitz’s many other careers: science journalist, columnist, lecturer, EFF policy analyst, non-fiction writer (their latest is 2024’s Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind), co-host of the Hugo Award-winning Our Opinions Are Correct podcast (with frequent creative partner Charlie Jane Anders), and former editor-in-chief of io9 and Gizmodo.

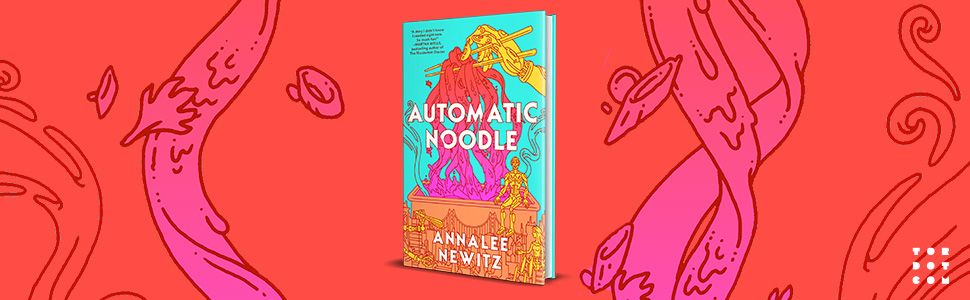

The weight of some of these ideas and the complications behind them can make for heavy reading. But Newitz’s fourth novel, the newly released cozy science fiction story Automatic Noodle, is a lighter take on similar topics. The book centers on a handful of robots left over from the war after a liberated California secedes from the rest of the United States. Operating in secret, fearing anti-bot prejudice and the possibility of being reclaimed as property, they set out to make the money they need for independence and self-ownership, and navigate their own individual traumas and identity questions along the way. Polygon sat down with Newitz ahead of Automatic Noodle’s release to discuss the book’s unusual relationship with food, robots, sexuality and gender, and even the “cozy” label — call this one “complicated cozy,” because there’s a lot going on here.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

Polygon: This book feels like such a departure for you, at least in terms of its lighter tone and much smaller scope compared to your other novels. Did it feel like you were trying something different?

Annalee Newitz: It was definitely a departure for me, in some ways that might seem kind of mechanical. It’s the first novel I’ve done where we follow the same characters all the way through — usually I’ve either been bouncing back and forth between points of view, or I’ve had something where we follow one character, then a different one, then a different one.So I was like, “OK, it’s going to be an ensemble cast, and we’re not going to switch back and forth between POVs. We’re just going to always be with the ensemble as much as possible.” That was actually very relaxing. It was easier to put together. But [this book is] in some ways deeply connected to a lot of the themes I was already developing in Autonomous and The Terraformers.

It certainly feels like you’re still exploring the same things, in new ways. But I’ve never thought of your books as cozy or comforting before Automatic Noodle.

It’s being marketed as cozy, and I don’t think that’s wrong. I love cozy fiction, and I love cozy movies as well. I had just finished writing Stories Are Weapons, a non-fiction look at culture war in the United States, and honestly, that book was so traumatizing to write. I spent three years basically immersed in how people traumatize each other, and I wanted to write a book about recovering from trauma.

I think the very best cozy writing — the cozy writing I find myself really drawn to — isn’t just friendly and light. It’s about people who’ve had horrible things happen to them. Maybe people who are in the midst of something really horrible, but who find comfort and solace and a space of calm and warmth. And that was what I really wanted this book to be. Because I think all of us see a lot of darkness and trouble coming our way, and I was like, “How about if this book is set five years after the war is over, and we’re now rebuilding?”

I really wanted to lean into the rebuilding feeling, because maybe if we can collectively, as civilizations, focus on the rebuilding vibe, we can just skip right over the war part, and just start rebuilding now. Because there’s plenty to rebuild. We don’t need to break any more. So to me, coziness is recovery.

There’s a lot of trauma in this book. I was a little worried when I was talking with my editor about it being [labeled as] cozy. I was like, “Well, there’s some pretty rough stuff.” So I think it still has some darkness. But yeah, it’s definitely focused on “Let’s come together in the wake of horror.”

What’s some of your favorite cozy fantasy or science fiction? What would you point other people to?

A lot of the stuff I was thinking about when I was writing this — I had been reading a lot of Nghi Vo. Her Singing Hills Cycle, I think of as being my kind of cozy. [Those books are] still pretty spiky, but they also have this element of warmth and discovery. And of course, Malka Older’s recent series, the Mossa and Pleiti series, which are cozy mysteries set on Jupiter. Malka is a friend, but also, I’m a fan of her work. And I was a fan before we were friends, so I’m O.G. Those books really inspired me a lot, because again, there’s this war lurking in the background. There are a lot of systemic problems. But at the same time, we focus in on characters who are in small ways trying to solve things.

Also, oh my God, I’m so obsessed with C.L. Polk‘s writing. It’s so funny — they write in a lot of different genres, and always have super-dark shit going on. But at the same time, there’s romance, and dealing with issues around oppression, and recovering from warfare. Their Kingston Cycle, the trilogy that has Soulstar in it, I think that was their first big trilogy. It’s sort of set in a secondary world that’s recovering from basically World War I, and it’s gay romance, super-hot gay romance with elves and all the things. But it’s also about resource extraction and abusive war veterans.

And of course, Becky Chambers — her Robot & Monk books, as well as her other series. Yeah, that’s the kind of stuff I was marinating in to feel better while I was writing about culture war.

Automatic Noodle also deals pretty significantly with culture war, specifically between California and the rest of America. I’m looking at a page in the book where one character says “I really don’t want to get sent back to America. Fuck that place. It’s a hellhole run by garbage cans.” And boy, does that feel like a familiar political sentiment right now. You may present this book as “The war is over and we’re rebuilding,” but this is also a setting where the subsequent culture war is highly active, and your characters are contending with it.

And the characters are dealing with robophobia, and one of the characters was a soldier in the war. I mean, they all served in the war in one way or another, but one of them is a stay-behind soldier, which means that it’s his job to basically remain alert to the possibility that there might be U.S.-backed insurrectionary forces in California that could come back and start the war again. So he’s hypervigilant all the time.

And for me, that’s a very relatable character, because I’m dealing with lots of PTSD, and I was like, “Good, OK, I can channel all my feelings.” And of course, that’s the thing about culture war — it’s the thing that keeps traumatizing us even after a total war has ended, or before a total war begins, or between wars. There’s definitely a whole subplot that’s directly inspired by my research into psychological warfare. I know exactly who these soldiers are. I’ve talked to guys and women like this, I’ve talked to humans who’ve served in these roles, and I can easily imagine a future robot serving in those roles.

And I really also wanted to — this is a deep cut, and I think maybe 0.0001% of people get this, but this book is also a reference to the early days of white settlement in California. In San Francisco, as white settlers were coming in — the United States occupied California, took over California from the Spanish, who had taken it over from the indigenous nations. So there were all of these vigilance committees in the late 19th century in San Francisco specifically, and they were moral organizations, very recognizable to us today, who were trying to stamp out sex work, basically, and also get rid of Chinese people.

They were super white supremacists, but the vigilance committees’ nominal goal was to keep San Francisco morally pure, because they were trying to transition the city from its gold-rush days to a more proper sort of place. So I brought back the vigilance committees and made them anti-bot. I threw that in there because ever since reading about the vigilance committees in San Francisco, I’ve been like, “Oh yeah, I recognize this. I feel like it’s just about to come back again. We’re going to have vigilance committees one day.”

At the same time, it feels like some aspects of this book are written from the heart about the process of making, tasting, and sharing food, and about food as a cultural expression. How much did that come out of your own experiences — your tastes in food, your interest in Northern Chinese cooking, or watching people prepare biang biang noodles?

All of the above. I have always loved noodles, ever since I was a kid. Definitely at various points in my life, my nickname has been “Noodle,” due to my obsession. And I really like chewy noodles, I really like wide noodles. I grew up in Southern California, where really excellent Chinese food was widely available, because there was such a big immigrant population, people coming from all over China. I grew up with my dad taking me to Chinatown in LA, where he grew up — I mean, he grew up in LA. He didn’t grow up in Chinatown.

So from childhood, I always had this feeling of being an outsider who was a big fan of a culture that wasn’t really mine. I think a lot of people who grow up in areas with lots of immigrants probably feel that way, because you’re exposed at a young age to a bunch of cultures that aren’t really yours, but you grow up with them. And so you have comfort food — it isn’t from your own culture, but it’s still your comfort. I wanted to capture that feeling with the robots of like, “Well, there is something comforting about this aspect of human culture. We’re not human, but we still love it, and we still want to respect it.”

When I was working on the book, I showed drafts to some friends who were experts in cooking, but also to some folks who were just doing expertise readings of it who were Chinese-American, or who had written a lot about Chinese-American food. I got a lot of good feedback, and that section of the book changed quite a bit, because one of the pieces of feedback I got was, “You have to talk about the history of these noodles. You can’t just consume the noodles, you have to explain where they come from.”

That was really fun. That led me down a big rabbit hole of like, “Oh, where are these noodles from?” And I learned all this stuff that’s not in the book about the relationship between wheat and Chinese cuisine, because wheat entered the cuisine much later than soy. There’s all this soy-based stuff, but then wheat came in, and in the medieval era, the Tang Dynasty era, people were writing poems about, like “Dude! Wheat! Oh my God, wheat noodles are so amazing!” So that was really cool.

But yeah, that aspect of the book is all very authentic to my experience. I’m a huge — I don’t call myself a foodie, because I’m not sophisticated. I just really like food, and I really like comfort food especially. So I don’t go to the elevated restaurants. I like to go to a hole in the wall and just have a big fucking plate of noodles.

How did you come to this idea of characters who don’t consume food, but are trying to perfect food?

I wanted to think about — we have a lot of prescriptions among humans about how we’re supposed to experience pleasure and food. We’re supposed to experience the pleasure of food, really by eating, by consuming it. And there is a robot, Cayenne, who is able to actually taste all of the food and appreciate the flavors. And Hands has this exquisite ability to experience texture. And of course, especially in Chinese cuisine, texture is a really big deal. How chewy something is actually part of the aesthetic. And that’s part of what makes biang biang noodles so amazing — they’re chewy in this really special way. And so I wanted to think about, “What does it mean to take pleasure in something the ‘wrong’ way?” It’s like, “Oh, you’re not eating it, you’re just tasting it. What’s wrong with you?”

And I mean, look. There’s a pretty fricking obvious metaphor for being queer running through this book. There’s robophobia, which I was like, “Is that too on the nose? I don’t even care.” So these are robots who have a queer relationship with food, and they’re still getting pleasure out of it. And most of all, they’re using the food to create a community space where humans and bots can come together and figure out, coming from their very different places, how to have appreciation for each other.

Maybe in an ideal world, [the robot characters] wouldn’t have to make food [for humans]. Maybe they would have something that they could do just for robots. But they do, over time, figure out how to make the space available to robots. And so I think that was really my motivation, to say, “You know what? You can take pleasure in things in many different ways, and you don’t have to follow the rules.”

The thing I most see running through all your fiction is the idea of personhood, and who or what is a person — your work is full of animals or objects or other outsiders who are people, but have to fight against the dominant culture to be recognized and respected. And they tend to form their own supportive bonds and communities. Which takes us back to the queerness metaphor, except it all comes through a lens of AI ethics. Why has personhood and identity been such an area of exploration for you?

It’s not just me — it’s kind of in the air. Because especially when it comes to robots and AI, a big question in those areas is personhood, just from a scientific or engineering perspective. But I’ve always been interested in the ways people can imbue many, many objects with personhood while still denying the personhood of people.

I just think one of the fundamental problems we experience — if there’s any kind of universal thing that one can write about or think about — there are so many permutations of how we dehumanize people. We know they’re fucking people! Why do we keep saying they’re lesser? It’s just so arrogant.

So I hope I can create worlds where people come away thinking there are a lot more people around them than they really realized. And it goes beyond queerness — it has a lot to do with race and national status, like immigrants. Again, I grew up in California, so I was surrounded by immigrants, some of whom were undocumented. And there were all kinds of political conversations and informal conversations about who counts as a person, who counts as a voter, who counts as an American.

So exploring this topic is my way of working out what’s happening to us under capitalism, under nationalism, to mutate our idea of who people are. It just seems like it’s so simple. People are obviously everywhere, and we set up all these rules that are just completely absurd. So I like to tweak them and overturn them and get people to think about how absurd those rules are, and who’s being hurt by them. So that’s why I always want to have characters who are super-vulnerable and emotional and relatable, who are constantly being told that they’re not really people, so that the reader can be like, “Oh yeah, that’s fucked up. Maybe this is a person, and maybe they shouldn’t be abused or put into a prison.”

Your fiction also tends to explore aspects of gender, especially how individuals identify, and how outsiders identify or label them. And dealing with robots lets you play around with that, while getting away from current politics, and the government’s obsession with—

[Laughs] Regulating human gender?

That’s a good way of putting it. So here you have characters who in some cases have been designed to be identified as certain genders that may not match how they see themselves, and at least one of them engages in body modification to escape that. Do you think of writing robots as naturally connected to writing about gender?

It definitely is. For me, what I think is most interesting from the gender perspective is, robots are easily modified, and they have lots of different morphologies. So it’s a way of literalizing how it feels to be in a body that doesn’t fit the ideal cultural notions of what your body should look like. As someone who’s non-binary, I’ve always felt kind of puzzled by how my body works, how people respond to it, what it’s supposed to look like. And I’m bombarded with messages about what it’s supposed to look like that don’t feel right to me physically or emotionally.

And lots and lots of other people feel that way, not just people who are trans and non-binary. I think almost everyone feels that way at some point: “Oh, my body doesn’t really match how I see myself,” or “I’m feeling things in my body that don’t fit what I’m supposed to feel.” And I think with robots, you can literalize that. You can be like, “Well, this robot has three legs, and she’s experiencing things really differently.” And the kinds of modifications the character Sweetie is able to do — I got to write the world’s greatest top surgery scene, just like, “Oh, you want top surgery? Boop! Done!” I had had top surgery a few years ago, and I was like, “I wish it was that easy. The two-month recovery period, I could do without.”

I guess the final thing I would say about that is that the problem with gender [policing] is that it divides the world up into two kinds of bodies, and that’s it. And that’s not how the world is! We have so many kinds of bodies just among humans alone.

And so with robots, it allows us to kind of get outside that gender box and be like, “Oh yeah, there’s ways of being physically different that have nothing to do with our genitals, and nothing to do with our reproductive abilities.” We can be in a wheelchair. We can be tall or big in different ways, or small in different ways, or whatever. Only have one arm. This is all totally normal stuff. But of course, we always just want to stamp gender onto everything, like “All difference comes from gender or race!”

This feels like a standalone story, with a beginning and an end. But it also feels like there’s still a ton left to explore — threats the characters are still facing, an uncertain setting, relationships still in the early stages. Are you planning sequels to Automatic Noodle?

Well, it is set in the same extended universe as Autonomous, my first novel, and The Terraformers. Obviously separated in time, but it is intended to be part of that whole sequence of stories that I’m telling about robot civil rights, and humans gradually becoming de-centered over time. This is maybe the fourth or fifth thing I’ve written that’s set in that kind of vague timeline. So I’m sure I’ll be back — maybe not with these characters. I mean, we’ll see if there’s some enormous, huge demand. I could imagine writing another novella set in this restaurant, or set nearby, or something like that.

But for now, I’m already working on my next novel, and it is definitely not set in the robot-human timeline. It’s about a grad student from beyond our galaxy — actually lives in the gas cloud that surrounds our galaxy — and they’re doing their graduate work on Earth. And so they meet some humans and have some participant/observer adventures. So it’s very different — but it does involve lesbian tentacle sex. So I can promise you that there will be some good morphology follies. [Laughs] Yeah, excited about that. Excited about the lesbian tentacle sex. I’m kind of waiting for that scene to happen, so I’m writing toward that scene.

Do you have a title?

The working title — it’s subject to change, but currently it’s called A Wall is Also a Road. And we’re going to hopefully going to have that finished at the end of the year, and then we’re hoping that that’ll come out in 2026. Obviously I haven’t finished yet, but that’s what we’re hoping. It’s going to be slightly cozy as well. And then I’ll get back to writing spikier stuff after that. I’m under contract for a couple more novels after that, that are going to be a little bit more Terraformers-like.